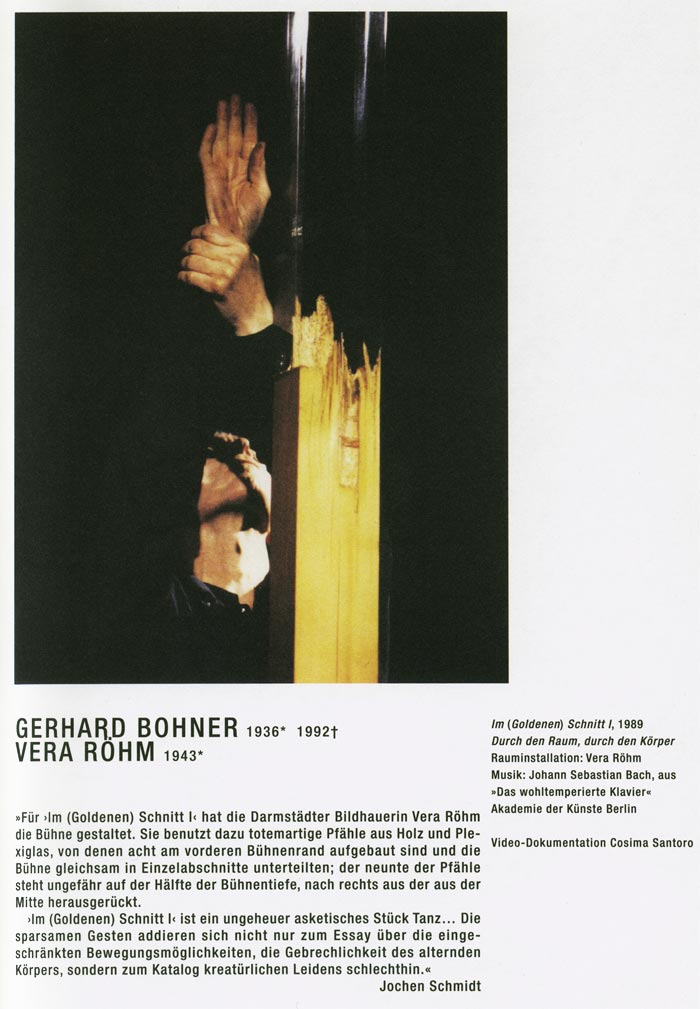

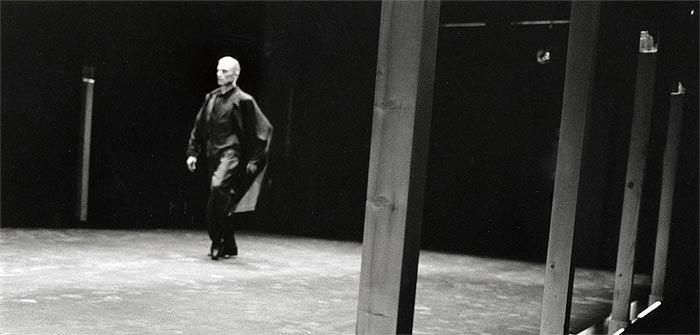

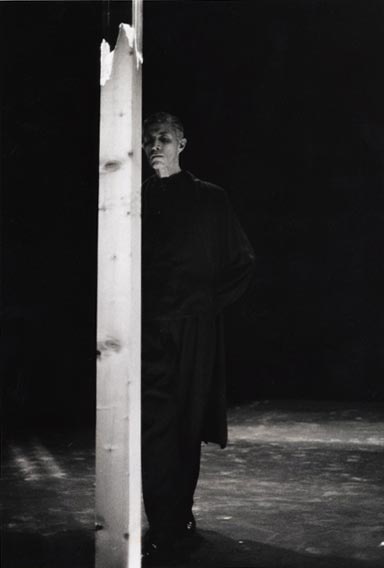

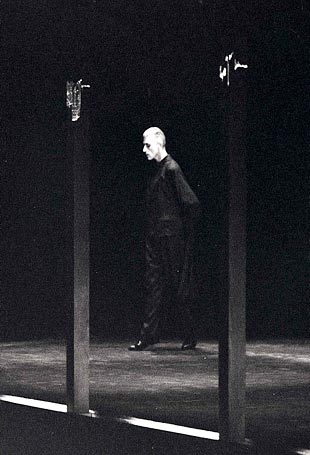

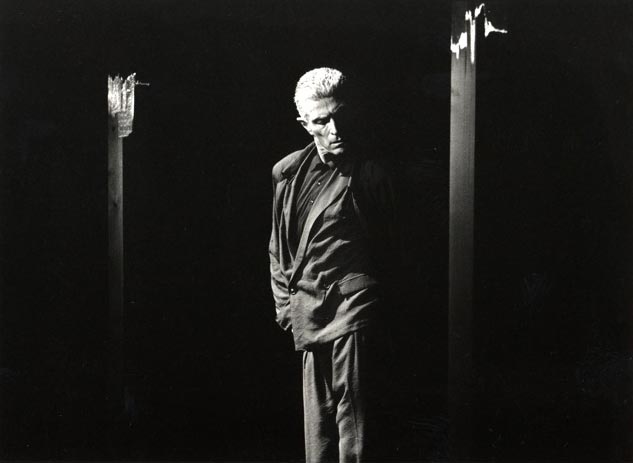

For ‘In the (Golden) Section I’, Darmstadt-based sculptor Vera Röhm designed the stage. To this end, she made use of totem-like poles made of wood and Plexiglas, erecting eight of them at the front edge of the stage and thus essentially subdividing the stage into individual sections. The ninth of the poles is placed about half way back on the stages, somewhat to the right of center.

‘In the (Golden) Section I’ is an incredibly ascetic dance piece… The sparse gestures add up not only to form an essay on the constrained opportunities for movement, on the fragility of the aging body, and to offer a list of creaturely suffering per se.

Jochen Schmidt

Körper – Leib – Raum, Der Raum im zeitgenössischen Tanz und in der zeitgenössischen Plastik, Tanz x Skulptur x Raum. Ein Lexikon von Nele Lipp. Uwe Rüth, Skulpturenmuseum Glaskasten Marl, Art Print Publishers, Essen (ed.), 2005, page 27

German sculptor, photographer and stage-set designer, born in Landsberg/Lech and grew up in Geneva. She studied in Paris and Lausanne. Since 1975 she has been working with compound materials using wood and Plexiglas, and calling them rod- or material supplementations. She starts with dramatically splintered rectangular wooden beams, the fissures and tears in which are visually pointed up by supplementing sections of an analogous shape made from transparent acrylic material. The clear structural shapes of rods, stele and geometrical configurations are contrasted by the suddenly refracted light, and the realms of the organic and geometric thus combined.

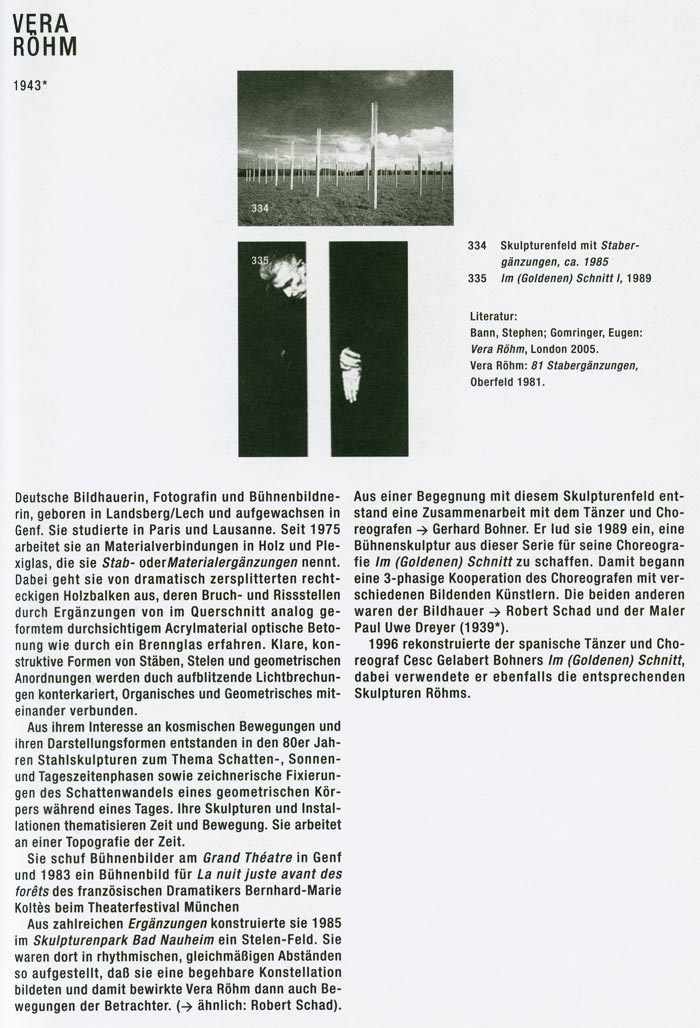

Her interest in cosmic movements and their representation led in the 1980s to steel sculptures on the theme of shadow, phase of sunlight/daylight, and drawings that set out to define the change in the shadow of a geometric body in the course of a day. Her sculptures and installations highlighted the subjects of time and motion.

She worked to create a topography of time.She created the stage-sets for the Grand Théatre in Geneva and in 1983 the set for La nuit juste avant des foréts, written by French playwright Bernhard-Marie Koltès and performed at the Munich Theater Festival.

In 1985, she brought together countless of the Supplementations to create a field of stele in Skulpturenpark Bad Nauheim. The stele were erected in rhythmic, regular intervals such that they formed a constellation visitors could walk through and also prompted movement among visitors (-> like Robert Schad).

An encounter with this field of sculptures led to collaboration with the dancer and choreograph -> Gerhard Bohner. He invited her in 1989 to create a stage sculpture from the series for his choreography In the (Golden) Section. This marked the beginning of three phases of collaboration between the choreographer and various visual artists. The two others were sculptor -> Robert Schad and painter Paul Uwe Dreyer (born 1939).

In 1996, Spanish dancer and choreographer Cesc Gelabert reconstructed Bohner’s In the (Golden) Section. In the process, he made use of the corresponding Röhm sculptures.

Körper – Leib – Raum, Der Raum im zeitgenössischen Tanz und in der zeitgenössischen Plastik, Tanz x Skulptur x Raum. Ein Lexikon von Nele Lipp. Uwe Rüth, Skulpturenmuseum Glaskasten Marl, Art Print Publishers, Essen (ed.), 2005, page 209

BODY PRESENCE SPACE

Uwe Rüth

Space in contemporary dance and in contemporary sculpture

Space is the external human experience. Opposed to it is the internal world of emotions and thoughts. Physical presence merges the internal and external worlds; the senses extend beyond all physical boundaries and out into space. Space is revealed to the subject through the bodies within it and the human presence moving through it. The space surrounding man therefore becomes the existential space of all that lives within it.

The above few sentences define the status of man as an experiencing being in the world. Since the beginning of the modern era, European man has been continually expanding his spatial experiences and relationships: discovering new worlds outside of the old and familiar world, discovering the space of his physical presence as an independent, directly associated and self-contained part of the world in which his ego is embedded: “As my body moves in space,” writes Henri Bergson, “all the other images vary, while that image, my body, remains invariable. I must therefore make it a centre, to which I refer all the other images.” (Henri Bergson: Matter and Memory, French, Paris 1896. Cited in: Dover Publications 2004, p. 43).

In his attempt to depict the external world, ever since the 14th century with the invention of the central perspective man has acquired a requisite know-how that up to a few decades ago was considered explicit and firmly set in stone. Only with the new discoveries made in the natural sciences since the end of the 19th century did this hitherto secure foundation begin to crumble. Moreover, Albert Einstein’s Relativity Theory that defined space not as straight but curved radically changed our view of the phenomenon of ‘space’ that is closely related with time.

It was after all the visual artist – in other words, creative man who set himself the task of interpreting and permeating the world by transforming matter into tangible and visual works of art – who in the course of the centuries documented and interpreted through art the changing perception of space in his images. While the two-dimensional depiction of space in a painting or drawing is an illusion, the sculptor by adding the third dimension always works directly in real space. This has remained until the present day: Whereas the painter, using form and color only for the creation of his abstract works, portrays man’s internal images to the outside world, often with spaceless compositions of forms and colors, the sculptor is limited to the creation of bodies for the space and in the space: The classical sculpture is an artistically crafted body that through its form and the expression conveyed therein fills and impacts the atmosphere of space. In the 20th century a trend emerged that intricately meshed the relationship between sculptural artwork and the space surrounding it until, ultimately, in the 1960s space installations and performances the surroundings became more and more part of the actual artwork. It was in the same decade that the artist realized the connection between the human body and how it emotionally related to the surrounding space. Sculpture and the human body thus came to be perceived as immediate parts of space that influenced it in the same way that, conversely, space influenced sculpture and the body.

A similar change of perspective emerged in modern dance, which in the second half of the 19th century more and more set itself apart from classical ballet, for the dancer’s body moving in space: “The key function of the ‘vacating’, the highly charged intermediary space between the elements of spatial composition, is accorded central significance in 20th century modern dance,” writes dance scholar Gabriele Brandstetter (Gabriele Brandstetter: TanzLektüren ‑Körperbilder und Raumfiguren der Avantgarde, Frankfurt a.M. 1995, p. 318) on the similar phenomenon observed in dance. In this context, it is worth mentioning the trailblazing US artist Loie Fuller who with her illuminated fabric dances in the late 19th century came to be regarded “as having pioneered and shaped this new relationship between movement and space” (Brandstetter, l.c., p. 332). The dancer’s movements and her flowing dress cascading in the air conveyed essentially new and comprehensive impressions and sensations in the space illuminated by changing colored lights. What for sculpture is the influence and integration of the surrounding space by means of static, artistic bodies placed within is for modern dance the moving and acting physical presence of the dancers: body – presence – space converge to form one combined artistic expression that as a whole affects the experiencing or immediately integrated spectator.

From the very outset there has been mutual influence or cross-fertilization of the two genres, namely the visual arts and modern dance. The first protagonists of modern dance often performed in museum rooms, usually in the immediate vicinity of classical sculptures, just as, conversely, artists and poets were ardent admirers of dance, such as Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin through to Rainer Maria Rilke and Hugo von Hofmannsthal. For example, US dancer Isadora Duncan repeatedly performed in the immediate proximity of Ancient Greek sculptures and, in her performances, often carefully emulated the stances taken by the classical figures or those portrayed on painted Greek vases: After all, the latter were regarded as the epitome of an intellectual and yet innocent and natural potential for movement. These elements of the immediate encounter of the presence of movement that appropriates space and the sculptural artwork as a body in space formed the most convincing examples of the artistic permeation of space. Here, the visual arts meld with dance and modern dance with artistic sculpting. This is the reason why in the field of dance performance in the visual arts (Gisela Brodbeck, Susanne Kirchner et al.) can be just as much considered contemporary dance as, conversely, the reduced formal canon of late dance as in the oeuvre of Gerhard Bohner can definitely be understood as dance within the visual arts. As both areas work with “the body in space”, there is a quite obvious if astonishing link between these two genres.

Yet where do we find the dividing boundaries? Do such exist, or are the transitions in fact so blurred and organic that they simply cannot be perceived? The exhibition “Body – Physical Presence – Space. Space in contemporary dance and in contemporary sculpture” seeks to provide answers precisely to these questions.

Versatile and vibrant, the exhibition program comprises several areas each of which employ different means of presentation. Let us begin with a part of the exhibition that is nearest to a museum dedicated to sculpture, namely sculptural works directly related to dance. This part has been limited to examples that illustrate individual and quite distinct relationships to the living body and its movement structures. This section could have easily been further extended. Limiting it to few striking examples that in their physical relationship are closely linked with ‘dance’ and thus to man’s ‘physical presence’ nonetheless seems more effective in that their exemplary nature will be perceived by visitors as a more intensive, stand-alone experience. Only few requested works could not be included for various reasons. The gap in the overall presentation is not so large, however, that it stands in the way of the objective being fully achieved.

The second area consists of works that occupy the ‘virtual’ space as artworks, namely the space that in recent decades has been made accessible through electronic media for the visual arts and modern dance (video dance) alike. The selected examples have created or depict own spatial structures that explore new environments and/or possibilities of movement for the human body. As before, a comprehensive and complete presentation was not the intention – the wide range of possibilities is strikingly illustrated by the examples on show.

Moreover, in the second part of the exhibition two examples of choreographed dance will be permanently shown from January 22 through March 12. A particular visual artist’s work (Vera Röhm or Robert Schad) is juxtaposed with a dancer (Gerhard Bohner) ‘in the (Golden) Section I and II’. Structuring the (stage) space, the original sculptural works made for the performance are placed facing the video documentation of the corresponding dance performance. The confrontation thus created attributes to the static sculptures and the dancer’s movements related to them a value of utmost authenticity.

Six dance performances on the theme of the exhibition complete the presentation. The aim is to identify and illustrate each typical space setting and the effects of sculptural elements that in selected performances play a pivotal role, and to understand their interactive value for the choreography.

The project will conclude with a theoretical permeation of the experiences made during the exhibition: On Saturday, March 11, a science symposium on the theme of the exhibition will be held in cooperation with the TanzKUNST study group of the Gesellschaft für Tanzforschung (GTF, Society for Dance Research), while the finissage on the following Sunday shall mark the end of the exhibition.

The aim of the catalogue presented here is two-fold: For one, like all exhibition catalogues, it documents what during the weeks of presentation will be on display and happening. Moreover, thanks to the lexicon “Dance x Sculpture x Space” compiled by dance scientist Nele Lipp it is also a magnificent work of reference.

Uwe Rüth, Körper – Leib – Raum, Der Raum im zeitgenössischen Tanz und

in der zeitgenössischen Plastik mit Tanz x Skulptur x Raum. Ein Lexikon von Nele Lipp.,

Uwe Rüth, Skulpturenmuseum Glaskasten Marl, Art Print Publishers, Essen (ed.), page 9

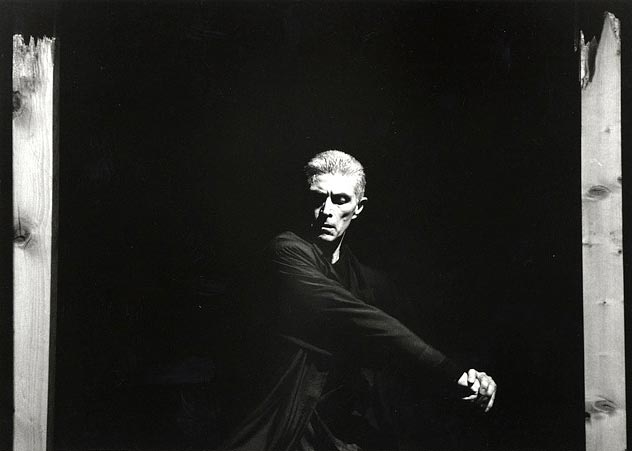

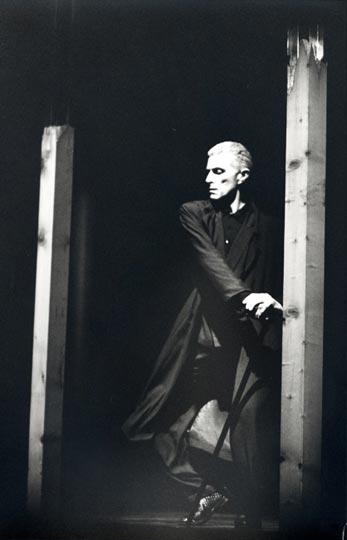

Im (Goldenen) Schnitt I, Durch den Raum, durch den Körper, debut performance 5/2/1989 Academy of the Arts Berlin, choreography and dance: Gerhard Bohner, Spaceinstallation: Vera Röhm, 9 complements, 1989, fir wood, Plexiglas, 315 x 11,5 x 11,5 cm each, Photos © Klaus Rabien (1,2,4,5,8) Gert Weigelt (3,6,7,9)

Oberfeld 1980

© Vera Röhm, Installation Oberfeld, 1980, 81 Complements, fir wood, Plexiglas, 315 x 11 x 11 cm each; distance 3 m each, 576 m2, Photo © Günter Claus

The Complements of Vera Röhm

Anca Arghir

In the early 1970s the sculptor Vera Röhm started work on a series of geometric objects consisting of fractured wooden beams that had their missing sections made up with transparent plexiglass. These have since become known as 'Complements'. Each of the squared, linear basic units meets the acrylic glass at a slightly different location and angle so as to achieve a series of variously modified structures. These, in turn, are produced on different scales. In the resulting complex images the material complementarity of wood an acrylic glass, and thus also that of nature and artifact, its itself 'complemented by the stylistic complementarity of constructive and expressive elements, for the points of fracture counter the smooth geometry of the whole with the drama of destructure counter the smooth geometry of the whole with the drama of destruction, as it were in vitro.

Vera Röhm's large-scale works have themselves been combined into even lager ones, and with these the spectator can interact. Within the multi-dimensional space thereby created, he or she can experience the two-fold effect of the 'Complements', as if by a process of synasthesia. It was precisely this simultaneous contrast of opposites that appealed to the dancer and choreographer Gerhard Bohner, who has used the 'complements' as a stage set for his solo dance 'In the (Golden) Section I . Though space, through the body'. The 'Complements', themselves both space and body, are intended to mark the stages through which the body passes during its irreversible progress through life.

In the (Golden) Section I

Anca Arghir

Through Space, through the Body

Only the installation of the wooden and plexiglas beams gives an insight into the space process which the „Integrations" evoke, apart from the intriguing effects of the light rays. Here they are positioned in rhythmical, regular intervals and in such a way that they constitute a kind of landscape physically accessible to the visitor.

Thus the aesthetic experience is not produced by a single object but rather by the synergetic moment of the total impression. From behind the wings, so to speak, the artist devises and directs a ceremony of pacing.

1987 Anca Arghir: Die Ambiguität des Gegenstandes in: Vera Röhm. Ergänzungen/Intergration, Galerie 44, Kaarst.

In the (Golden) Section I

Hedwig Müller

Bohner continued to address his theme of the dancer’s identity with equal consistency in the three versions of the production “In the (Golden) Section”. The friction with the institutional framework of the theater business, which was still present in “Show black white” (Schwarz weiß zeigen), however, is gone. In its place stands a work of art which now creates the outer frame and, on an even higher level, the confrontation with an aesthetic principle, namely the principle of what is considered harmoniously proportioned, as the title “In the (Golden) Section” indicates. When applied to the human body, the rule of the golden section, which states that if two sections of a straight line are placed in a harmonious relationship to each other the smaller section will always be to the larger as the larger is to the whole line, reveals that the point of division will always be approximately the center of gravity, the center of all dance movement. For Bohner, the relationships which result from the proportions and relations of the human limbs to each other and to the body as a whole are the content of his artistic work. Thus we may read the title of his solo evening without the parenthesis as well: “Im Schnitt” [a German idiom meaning “on average”]. The three parts of “In the (Golden) Section” are a kind of summing up of his work up to that point.

In the first part, with the spatial installation by Vera Röhm, a sculptor who works in Darmstadt and Paris, eight solid wooden stakes stand in the darkness like fence posts along the forestage, with a single one in the right rear of the stage area. These “Integrations” [Ergänzungen] open up various possible interpretations: the combination of wood and plexiglass at once combines and contrasts the natural and the synthetic, traditional and modern materials, the archaic past and the technological present. The broken has been repaired, the prosthesis completes the stump, the force with which the massive wood was broken off is still visible at the sharp split ends, at once monument and threat. The glass does not hide the wound but does shield it, it does not appease but makes it less dangerous. The stake set apart from the others determines the tension in the room, resisting – by its very isolation – the deceptively harmonious order of the other posts standing at attention, partially cancelling out the sober segmentation of the room by the posts in front, remaining present as an irritant, even when the events of the dance move away from it.

To the music of Bach’s “Well-tempered Clavichord” (in Keith Jarrett’s arrangement), Bohner reflects the sculptures which at the same time mirror his bodily images. In his choreography he shows the movements available to him as a dancer, no longer, however, with the eye of the young dancer, who would like to execute them as brilliantly and breathtakingly as possible, but rather as an experienced, mature man who is analysing the foundations out of which the movements, which extend into the room, have emerged, with all of their wounds which, however gilded, cannot deny the pain suffered. In the individual segments of the stage, each delimited by two sculptures, Bohner carries out his bodily analysis. Head, shoulders, arms, hands, legs, hips, knees, feet... All of the limbs are presented in their potential for movement, occasionally aided by a walking stick, which, to be sure, frees the leg being offered relief but points to disability and frailty. The images Bohner finds contain more than a sober analysis; they are not abstract, as the choreographic approach might lead us to assume. The circumspection with which Bohner dances, his handling of time and dynamics set new accents. When he puts his hands around his neck like a ring, with the tips of his thumbs touching, on one level he is showing us no more than the geometrical form of the circle, and yet he immediately awakens uneasy associations of being strangled to death. The forms of movement contain stylized everyday motions as well as sequences from classical ballet or expressive gestures – what he learned from Tatjana Gsovsky and Mary Wigman emerges here.

Excerpt from: Hedwig Müller: "Bewegungsskulpturen - Gerhard Bohners

Soloprogramme,"

Gerhard Bohner - Tänzer und Choreograph, Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1991,

pp. 115-16